The Swiss Open-Air Museum is – finally – getting a schoolhouse – Construction diary schoolhouse Unterheid

The schoolhouse in Unterheid, near Meiringen (BE), is currently being dismantled stone by stone so that it can be rebuilt at the Swiss Open-Air Museum. We’re keeping a construction diary, packed with all the latest about the relocation work, construction progress, the history of the building, background information and other interesting facts about this special project.

Construction diary entry no. 11, February 2026 – Hibernation on the construction site

In December 2025, the stove-fitter rebuilt the historic tiled stove from 1916 in the classroom and installed a fireproof wall behind it. The construction site then went into hibernation for the winter. So instead of reporting on construction progress in this blog post, we’re taking another short journey back in time to around 1830 – as we did in post no. 6 in February 2025.

If you’d rather experience the here and now, you can take a virtual tour of the museum building shell (as at November 2025).

What makes the schoolhouse from Unterheid, near Meiringen (Bern), so special? Part II: An eye-catching design

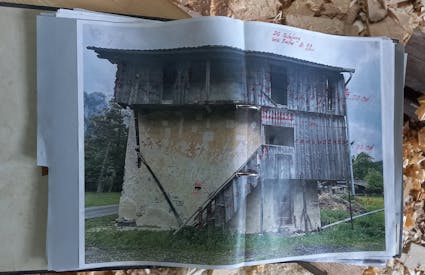

The schoolhouse from Unterheid is testament to the history of education in Haslital and Bern. Yet its appearance is not typical of the region. And there's a good reason for that.

The permission granted by the Church and School Council in 1828 and the assurance of financial support for the construction of a schoolhouse in Unterheid were conditional. Among other things, there were specifications regarding the materials to be used for construction. These were complied with and the schoolhouse was built out of stone. Only the roof structure, the half-timbered structure of some of the partition walls, the exterior porch, and the floors and wall panelling are made of wood. The roof was covered with slate shingles rather than wooden ones.

At the time of its construction, the schoolhouse stood out among the surrounding timber residential and commercial buildings built using logs. The only other stone structures in the surrounding area were mostly churches and vicarages. This makes it all the more significant that the schoolhouse from Unterheid was built as a solid structure.

The importance of the schoolhouse was further emphasised by the decorations in the form of a painted diamond effect on the corners of the building and an intricately decorated inscription in the gables. The building thus testifies to the growing importance of education in society from the 1830s onwards and the associated social change.

This part of the history of education in rural areas is now being given a permanent place at Ballenberg.

Construction diary schoolhouse Unterheid

The Swiss Open-Air Museum is – finally – getting a schoolhouse

The schoolhouse, a four-storey stone building with a slate roof, was built on the alluvial Aare plain in the Haslital valley in 1830. It served as a primary school for the children of the surrounding villages until the 1870s.

We first began drawing up plans to acquire the school building back in 2012. However, the idea of including a schoolhouse at the Swiss Open-Air Museum dates back much further, to around 1970, when the museum was still in the planning stages. The basic concept, back then, was to put together a representative collection of buildings from different rural regions of Switzerland and make them accessible to the public in one location. As well as traditional dwellings and ancillary buildings, the collection was to include the typical public buildings you might find in a traditional village. Naturally, this meant that a schoolhouse was a must. It took over 50 years, but we finally managed to locate and acquire a suitable property.

The historic school building goes on a trip: the dismantling process has begun!

It’s time! The starting whistle for the relocation of the historic school building from Unterheid has sounded, and the first steps have already been taken. The dismantling process has officially started, now that in-depth plans have been drawn up and bureaucratic hurdles overcome. Permits have been granted and there is nothing standing in the way of executing the project.

A building disappears – and a new chapter begins.

The first step was to demolish the annex, which is not part of the historic school building. The focus is now on dismantling the actual school building and the associated building inspection. The excitement is mounting: what secrets will the old building reveal? What stories are hidden in its individual components?

The first phase saw the pergola and the staircase be carefully dismantled. These pieces have been put into storage, with defective or missing pieces of wood being rebuilt already so that they can be reconstructed at a later date at the Swiss Open-Air Museum. The roof and interior are next on the agenda. From mid-June, the masonry will then be removed brick by brick – a precise and challenging task.

The foundation is in place in its new home.

In parallel with the dismantling process, foundations were laid at the new location in the eastern part of the Swiss Open-Air Museum. In the future, the school building from Unterheid will be rebuilt in the Bernese Oberland area, next to the pottery in the smallholder’s house from Unterseen, Bern (1051). However, the building needs a stable foundation before it can be relocated.

At its original location in Unterheid, the school building stood on soft ground in the alluvial area of the Aare and rested on a stone foundation. Over the course of time, this has led to substantial sagging on one side, resulting in a large crack in the masonry. The soil at its new location in the Swiss Open-Air Museum has different characteristics – some parts rocky, some earthy. A robust concrete foundation was chosen to prevent it from sinking unevenly. Made from concrete strips, this is intended to counteract the challenges of the uneven subsoil and provide the historical building with the stability it needs.

Dismantling and reconstructing a historical building are more than just technical processes – they are a tribute to the craftsmanship and history that is embedded in every stone and every beam. We look forward to following the progress and discovering the stories this building tells.

Step by step: the schoolhouse is dismantled

Work on dismantling the schoolhouse in Unterheid is proceeding at pace. Over the last few weeks, both the top floor and the second floor have been removed. Some interesting discoveries were made along the way: a drawing on a piece of wood and indications that the windows had been replaced at some stage and the jetty expanded in later years. This demonstrates that even in 1830, those working on the structure were professionals who understood their craft. Thanks to the digital twin, you can now embark on your own digital tour of the schoolhouse.

The dismantling operation is in full swing

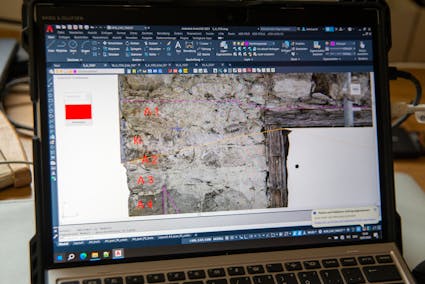

The original schoolhouse had a slate roof, which is to be reconstructed at the new location in the Swiss Open-Air Museum. The tiles that had lain on the roof for the last few decades were therefore removed. Once the components had been carefully numbered, the wood supporting structure for the roof was brought into the workshop, as was the historic panel in the schoolroom and in the teacher’s house. Next on the to-do list were the brick walls. Again, parts are being numbered, but not every single brick – given that there are tens of thousands, that would be far too many. Of the masonry, only the prominent, particularly large bricks that are important for the structure of the wall are being measured precisely and recorded on a plan, i.e. mapped. This task is being handled by the archaeological department of the canton of Bern, which is supporting the dismantling project. The individual bricks are cleaned of mortar and plaster and then stored separately by wall and storey so that they can be relaid in the correct places later.

Digital twin of the schoolhouse in Unterheid

As well as marking the individual components precisely and mapping them carefully on the plans, a digital twin was created for the reconstruction. This digital twin is a precise virtual representation of the schoolhouse based on photos, and was completed prior to dismantling. The technology enables us to look inside the premises at any time later on and study details that are important for the reconstruction. Why not explore the interior of the building for yourself? Link to digital twin.

Discoveries during the dismantling process

While the masonry was being dismantled, a piece of wood with a drawing symbolising a type of chalice was discovered. What this drawing is all about, and when it was made, is as yet unclear. Would you perhaps have an idea?

Outlook

By the middle of August, there will be nothing more to see of the old schoolhouse in Unterheid. Work will then begin on its reconstruction at the Swiss Open-Air Museum. We will report on the burning and slaking of lime in our next blog post. The lime will be used to make a special mortar for the reconstruction of the schoolhouse at Ballenberg.

The last stone has been taken down – now the reconstruction can begin!

Today – after just four months – there is not much left to see on the plot where the schoolhouse from Unterheid recently stood. The dismantling process was completed as planned, the timber elements are currently being restored in the carpentry shop and the stones are waiting in the open-air museum’s storage area, ready to be repositioned. Now it’s time for the next exciting, and lengthy, phase: the reconstruction will begin at Ballenberg on 26 August 2024.

Lime mortar – following in the footsteps of a millennia-old tradition

The stone walls are being constructed with a historical building material that is rarely used nowadays – traditional lime mortar. This is mixed right on the building site in the open-air museum.

There is evidence that lime mortar was used more than 10,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest artificially produced building materials in the history of mankind. It consists of burnt lime as a bonding agent, water and sand as an aggregate. The burnt lime used for the reconstruction is fired in the lime kiln in the Brandboden clearing (491) at Ballenberg.

These days, the construction industry favours faster-setting cement mortar almost exclusively, so pure lime mortar is very rarely used. Lime mortar takes longer to set than cement mortar. As a result, only a few layers of stone can be built on top of each other each week while the schoolhouse is being reconstructed. This means that it will take considerably longer to finish the masonry. The application of lime mortar in the reconstruction of the schoolhouse from Unterheid is reviving the old knowledge about making and working with this material.

The mortar recipe

To produce the mortar, sand and burnt lime are placed on top of each other in several layers and covered with water. This dissolves the lime and increases its volume, resulting in what is known as lime mortar. Lime inclusions – clumps of undissolved lime – form small reservoirs in the mortar mixture. Even if the mortar has hardened after being used in the masonry, it is nevertheless possible for lime to be removed from the inclusions by means of moisture. This lime can then fill any little cracks near the lime inclusions. In other words, the mortar mixture can repair itself to a certain extent.

Brick by brick– a jigsaw puzzle unlike any other

After being meticulously taken apart brick by brick, the schoolhouse is now being reconstructed just as it was in the past. The bricks, which were separated and marked when the building was dismantled to indicate which storey they were from and which direction they were facing, are taken from where they were being stored outside the museum to the construction site, where they are sorted. Thanks to the detailed plans prepared beforehand, the particularly prominent bricks can be returned to their original position. This is especially important at the corners of the building, as they are very important for the static equilibrium of the schoolhouse. The whole thing resembles a giant jigsaw puzzle in which the masonry is being carefully reassembled.

Almost like dry stone masonry

When the schoolhouse was built in 1830, the quarry stones were not hewn into blocks before being laid into position. This meant that there were hollows in the masonry between the unevenly shaped bricks, which were then filled with slate and mortar, just as they are today. When building the walls, it is also important to ensure that each brick touches at least three others to make sure the building is stable enough. The way the schoolhouse is bricked means that its walls could almost stand by themselves, without mortar, like a dry stone wall. This is because the loads are supported by the bricks themselves and not by the mortar. Nevertheless, mortar is needed to join the bricks together. The pure lime mortar used for the schoolhouse has a higher level of elasticity compared to modern cement mortar, which allows the building to compensate for minor movements in the masonry.

Lime mortar – straight from the construction site

Right next to the construction site is a specially equipped mixing site where the lime mortar is produced. The lime required for the lime mortar was fired in a lime kiln on the Ballenberg site. If you want to learn more about the fascinating process of lime burning, we recommend our article on the lime cycle.

Traditional techniques without any glue or screws

The reconstruction process is being carried out closely in line with historical masonry techniques. While the masons put the individual bricks together to form a stable wall, the carpenters work on the timber elements at the same time. Even during the dismantling process, these elements were carefully examined for damage and analysed to determine which parts needed to be replaced and reconstructed. As is customary at Ballenberg, the carpenters use traditional timber construction techniques. The components are connected using mortices and wooden nails, without any glue or screws.

Construction work is stopping for winter – but the construction diary continues

As winter approaches, Mother Nature will force us to take a break from construction work. As soon as temperatures drop below 5°C, it will no longer be possible to work with lime mortar and the Unterheid schoolhouse construction site will close for winter.

Waiting for warmer weather

Winter is calling the shots – at least on our construction site. While building work continues unabated in many parts of Switzerland, the Unterheid schoolhouse project at Ballenberg took a winter break shortly after the end of the season. This wasn't for planning reasons, but due to nature: lime mortar won't harden if temperatures are below 5°C. An early frost could have caused damage to the newly reassembled masonry. The early onset of winter at the end of November confirmed our decision to stop work in plenty of time.

Three quarters of the ground floor has already been completed. As soon as temperatures allow, probably in early April, construction work will resume and, if everything goes according to plan, the wooden boards on the first floor can be laid as early as May.

From plan to reality

Even before the Swiss Open-Air Museum first opened its doors in 1978, the idea of incorporating a historic schoolhouse into the building collection was conceived. According to the concept underlying the museum collection, such a building would be added to the rural dwellings. But it took decades for this vision to become reality. The search for a suitable building turned out to be more difficult than expected.

Finally, the schoolhouse from Unterheid was chosen. Starting in June 2024, it was taken apart brick by brick, in order for it to be reconstructed at Ballenberg. This initial step was completed in August. Watch a time-lapse video of the dismantling.

What makes the schoolhouse from Unterheid so special?

Although a schoolhouse was envisaged as part of the concept underlying the open-air museum collection right from the start, it was several decades before a suitable building – the schoolhouse from Unterheid – could be found and incorporated. It will be reconstructed at Ballenberg from the 2024 season onwards. But what exactly makes this schoolhouse a suitable building for the museum collection?

One of many schoolhouses in Haslital, but one of few in the Bernese Oberland

In 1835, the newly established Department of Education of the Canton of Bern adopted the Primary School Act, obliging municipalities to build schoolhouses. Until then, pupils in rural areas were not usually taught in purpose-built schoolhouses but in classrooms. These were located either in public buildings or even in private homes. Only a third of municipalities in the Bernese Oberland had their own schoolhouses.

Back in 1800, Haslital was already a major exception: each of its 15 school communities already had a schoolhouse. The density of schoolhouses in the region was comparable to that of the city of Bern. The number of schoolhouses in Haslital increased again from 1828, when the Church and School Council, which was responsible for education during the Restoration, approved and funded the construction of six new schoolhouses. These included the new schoolhouse in Unterheid.

Educational buildings

Many of these former schoolhouses have now disappeared. The surviving schoolhouse from Unterheid is one of the last remaining examples, which is testament to the intensive efforts to give schoolchildren in remote Haslital access to schooling. At Ballenberg, the schoolhouse will also represent a type of building that appeared throughout rural Switzerland from the 1830s onwards as part of the educational reform. Owing to the increase in the number of schoolchildren and the construction, as a result, of larger schoolhouses, many of the older buildings were later demolished or repurposed.

Start of the second construction season

Work on the schoolhouse building site resumed on 31 March, before the start of the season. April was actually much too dry and warm, which played into our hands. The relatively high temperatures and constant wind were beneficial for the lime mortar, allowing it to harden more quickly. This enabled more brickwork to be completed than originally planned, so the basement is almost finished. The carpenters have now arrived on site to insert the ceiling beams into the masonry. Scaffolding will be erected before the brickwork on the first floor can commence. The temporary protective roof also needs to be raised – after all, the schoolhouse will ultimately be almost 8.5 metres high.

Floor by floor - the construction is progressing

Since the start of the new construction season at the end of March, remarkable progress has been made on the construction site of the schoolhouse from Unterheid. With the ground floor walls completed, a section of the timber structure was next in line. Going forward, carpenters will be joining masons on site more often, with timber and stone construction now going hand in hand. The former have installed and bricked in the beams separating the ground floor and the first floor.

The first floor flooring that lies on top of these beams has also been laid. This was replaced with new materials because the planks of the old floor planks could no longer support the required load. The planks have been made to their original dimensions. The carpenters erected the original timber structure on top of the brick interior wall on the ground floor, which serves as the partition wall between the classroom and the hallway on the first floor. The masons are also in the process of constructing the parapets on the exterior walls, which will later support the window frames. The classroom’s window openings will soon be visible.

Floor by floor - the construction is progressing

Visitors to Ballenberg this season will be able to see the almost finished shell of the schoolhouse relocated from Unterheid, near Meiringen (Bern), at the construction site. Reconstruction is progressing rapidly, although bricklaying with pure lime mortar takes time, as only a few layers of stone can be freshly laid on top of one another at a time. However, it is important that we adhere to schedule given that from as early as October, the temperatures could drop so low that the bricklayers would no longer be able to continue working. At the moment, however, the biggest challenge faced is the ongoing heatwave. If the mortar dries out too quickly, cracks can form and the mortar crumbles. This is why the bricklayers cover the fresh mortar with wet cloths at the end of the day – this delays drying and curing.

The first floor flooring that lies on top of these beams has also been laid. This was replaced with new materials because the planks of the old floor planks could no longer support the required load. The planks have been made to their original dimensions. The carpenters erected the original timber structure on top of the brick interior wall on the ground floor, which serves as the partition wall between the classroom and the hallway on the first floor. The masons are also in the process of constructing the parapets on the exterior walls, which will later support the window frames. The classroom’s window openings will soon be visible.

Milestone achieved! The first construction phase is (almost) complete

Two summers and two Ballenberg seasons later, the shell of the schoolhouse from Unterheid is almost finished. The foundation stone for the three-storey brick building was laid in August 2024 and the final stone was inserted into the gables in November 2025. In recent days, masons and carpenters have been working alongside each other on the construction site once again. While the exterior walls were being completed, the timber roof structure for the schoolhouse was being assembled.

At its former location, the roof had been leaking for a long time and the beams were rotten in many places. The carpenters frequently had to use new timber during the reconstruction. Wherever possible, however, the original material was reused. The roof now has a multi-layer wooden shingle covering that will only be visible for a few months before another layer of slate shingles is fitted.

Despite the cold weather, the bricklaying continues, but only in the interior of the schoolhouse that can be heated. The half-timbered walls are being lined with brickwork and the exterior porch is being completed.

Anyone who has followed our blog may remember the interesting discoveries that came to light in the gable during the dismantling of the building: a drawing of a chalice on a piece of wood and a handful of dried green beans. We are not exactly sure, but it is quite possible that these were bricked in when the building was originally constructed in 1830. Inspired by these findings, we held our own little celebration with all the craftsmen involved in the reconstruction so far. In keeping with tradition, we embedded something else in the gable – but what exactly remains our secret.

The relocation is supported by the Ghelma AG Baubetriebe in Meiringen. Thank you very much!

The relocation is supported by the Burgergemeinde Bern. Thank you very much!

Ballenberg

Swiss Open-Air Museum

Museumsstrasse 100

CH-3858 Hofstetten bei Brienz

Opening hours Administration

3 November 2025 to 8 April 2026

From Monday to Friday

8.30 am to 11.30 am

1.30 pm to 4.30 pm

Opening hours

9 April to 1 November 2026

10 am to 5 pm daily